The COVID-19 pandemic forced us to reevaluate the value of nature and the emotional balance it provides us. It was a reminder that our communities include not just human residents, but all species that reside beside us. These “naturehoods” — green spaces around us no matter how big or small — hold astonishing biodiversity that thrives, regardless of the human condition.

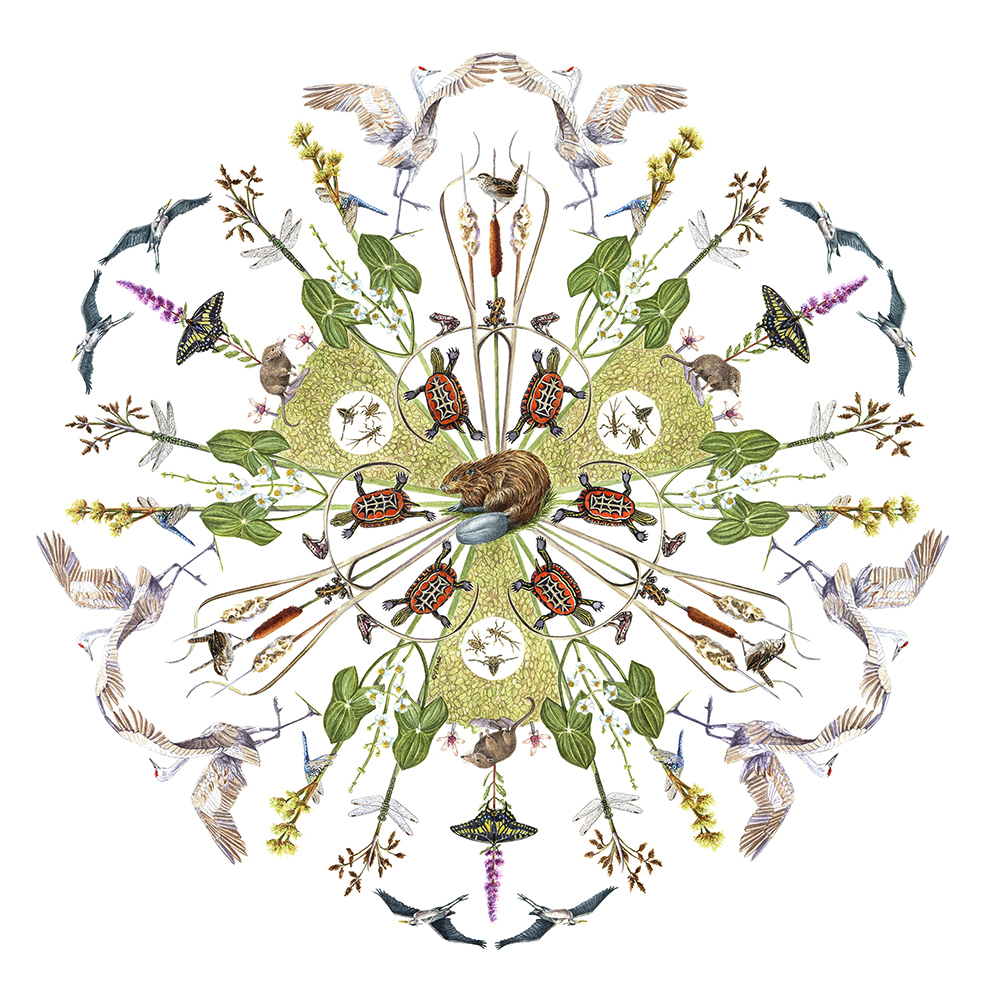

Mandalas are symbols of wholeness, characterized by concentric layers of shapes and images. They are tools to focus attention and contemplation. Creating nature mandala art is healing and can be transformative. Many people use mandalas as a tool for meditation and to regain their sense of self by connecting with the natural environment.

The focus of this project is to create a series of mandalas showcasing the communities of different ecosystems found throughout Metro Vancouver. Each mandala will include endangered and threatened species in each of those habitats with the goal of raising awareness for the fragile ecosystems that are part of our world. This project was made possible in part with support of AFC’s Rob and Sharon Butler Art Explorers Grant Program.

The Forest Mandala

This mandala highlights the “naturehood” of forest habitats found throughout Metro Vancouver, British Columbia. Twenty-five native species are featured, including those that are ecologically and/or culturally important to the area. Temperate forests are globally important and unique, yet they have been extensively cleared for hundreds of years with few large examples remaining intact. Temperate forests are critical to modulating water, nitrogen, and carbon cycles which helps balance the climate across the planet. Recent studies indicate they have become the main global carbon sinks which keep heat-trapping gases out of the atmosphere, helping to mitigate climate change.

Species highlighted in this Forest Mandala include: Keystone: Pileated woodpecker; Douglas fir; Pacific tree frog; Mycorrhizal network; Keystone & Endangered: Pacific giant salamander; Endangered: Northern spotted owl; Little brown bat; Townsend’s mole; Oregon forest snail, 9-spotted lady beetle; Threatened: Phantom orchid; Western screech owl; Oregon fairy shrimp; Ecologically/Culturally Important: Black bear; Douglas squirrel, Banana slug; Western red cedar; Red alder; Trailing blackberry; Salal; Fungi (Bracket); Sword fern; Yellow-spotted millipede; Tiger swallowtail; Recovered species: Bald eagle.

A keystone species is a species that is critical to the survival of the other species in that system and vital to the functioning of that ecosystem as a whole. Some ecosystems might not be able to adapt to environmental changes if their keystone species disappeared. For example, thirty other species rely on the pileated woodpecker for survival—or rather the holes they drill. A simple action that has multiple benefits for the ecosystem, including supporting nutrient cycling, managing insect populations, and manufacturing new niches for other species to occupy. They create opportunities for foraging, sheltering, and nesting. In this sense, the pileated woodpecker is engineering the ecosystem. Scientists consider the Pacific tree frog to be a keystone species as well as an indicator species. It is a keystone species because of the vital role it plays in the food webs through which matter and energy flow. It is an indicator species because its presence, population trends, or absence tells us a lot about the health of the ecosystems it inhabits. Douglas fir is also a keystone species that has great influence on the whole ecosystem. When the canopy of Douglas fir trees is removed, the understory plants are exposed to the elements and quickly replaced by plants more suited to harsher conditions, thus changing the entire ecosystem. Giant Pacific salamanders regulate food webs and contribute to ecosystem stability by playing a significant role in the global carbon cycle.

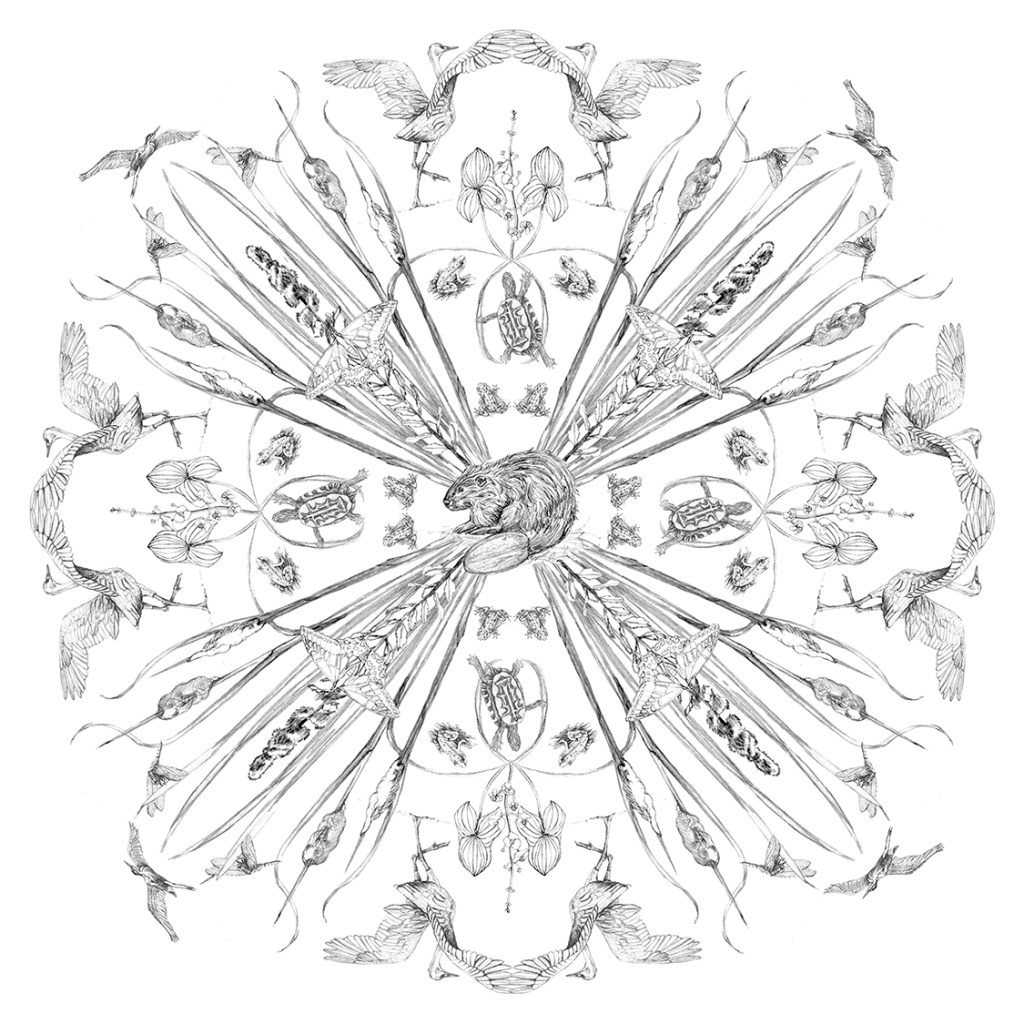

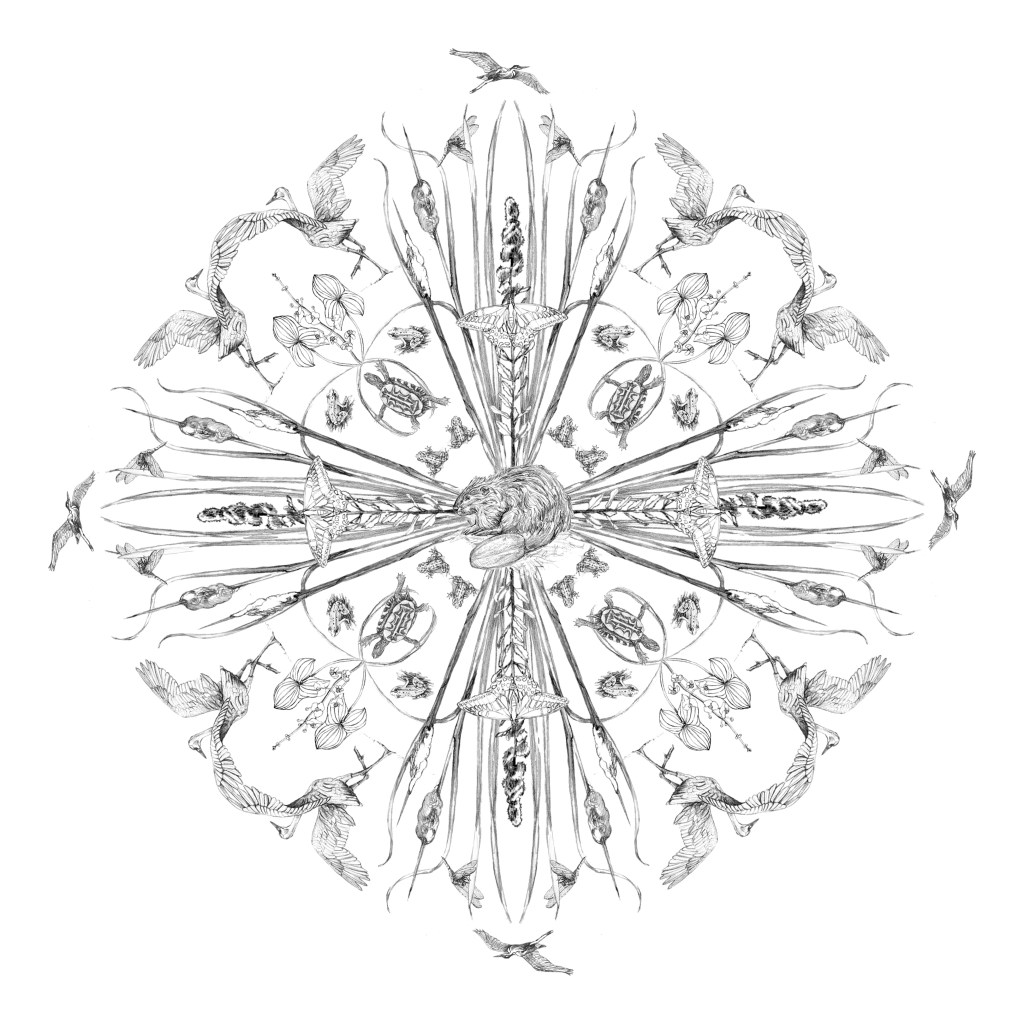

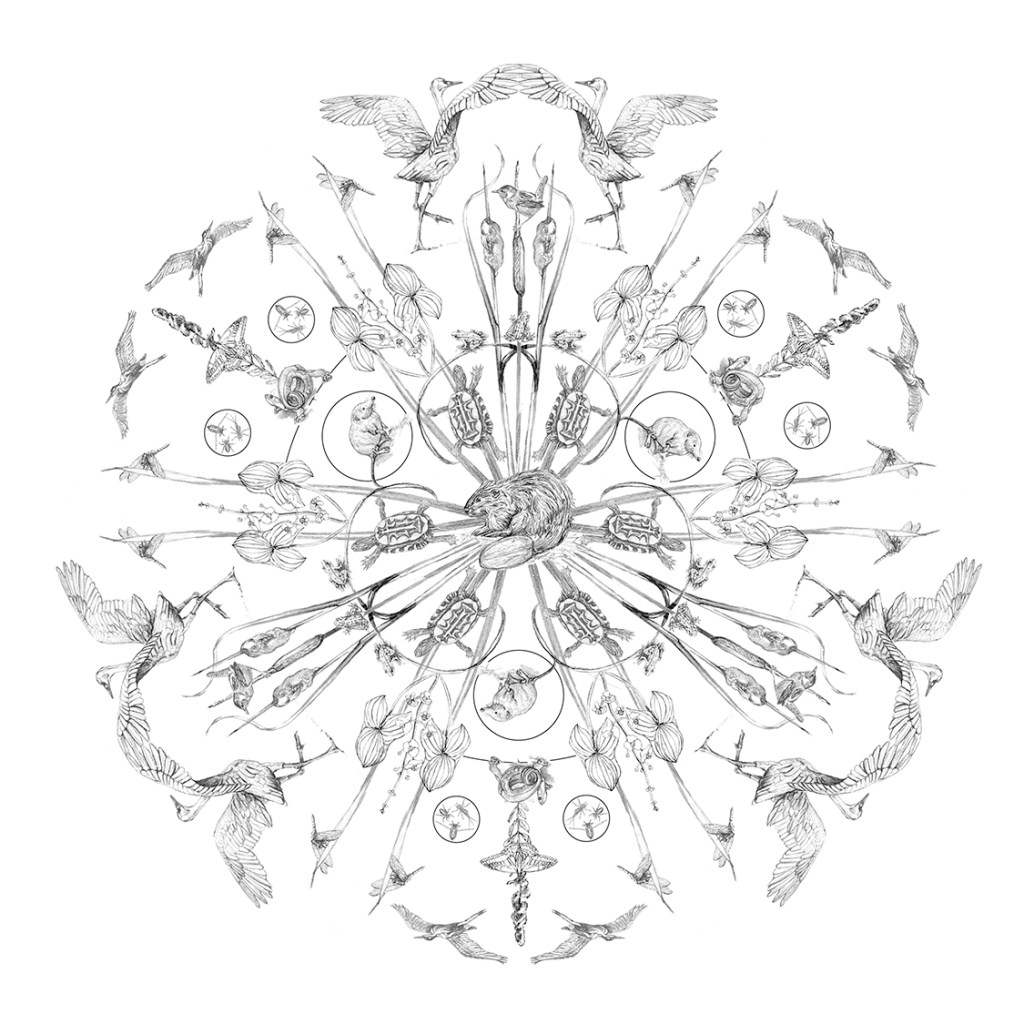

The Wetland Mandala

This mandala highlights twenty species found in wetlands of the Lower Mainland in British Columbia (see list below) and took over 300 hours to complete (including research, design, sketching, colour mapping and painting time). Read more about the importance of wetlands in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia and see some of the working designs at the bottom of this post.

Species highlighted in this Wetland Naturehood Mandala include: Keystone: Beaver; Endangered Western painted turtle, Western toad, Red-legged frog, Northern water shrew; Threatened: Great blue heron, Blue dasher dragonfly, Western pondhawk dragonfly; Species that are ecologically and/or culturally important: Wapato, hard-stem bulrush, spirea, water shield, cattail, duck weed, invertebrates; and Recovered species: Sandhill crane, Anise butterfly.

More Information About the Project

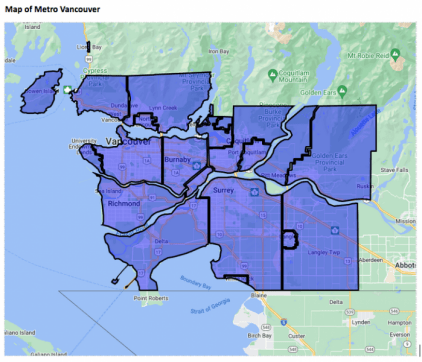

The Metro Vancouver Regional Park system holds incredible diversity and protects diverse natural landscapes and habitats. Park staff also host several informative, educational programs and various activities throughout the year (see calendar here). These parks are part of a larger system that includes regional park reserves, ecological conservancy areas and greenways. All of these places are located on the shared territories of many Indigenous peoples, including 10 local First Nations: Katzie, Kwantlen, Kwikwetlem, Matsqui, Musqueam, Qayqayt, Semiahmoo, Squamish, Tsawwassen, and Tsleil-Waututh.

I first search for species in each environment to sketch and photograph for reference, and also look for shapes and patterns that work well for mandala designs. After I create sketches and a “short list” of species to portray in each mandala, the design and painting process begins!

Wetlands

Wetlands are distinct ecosystems that are flooded by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). The water in wetlands is either freshwater, brackish or saltwater. The main wetland types are classified based on the dominant plants and/or the source of the water. For example, marshes are wetlands dominated by emergent vegetation such as reeds, cattails and sedges; swamps are dominated by woody vegetation such as trees and shrubs. Examples of wetlands classified by their sources of water include tidal wetlands (oceanic tides), estuaries (mixed tidal and river waters), floodplains (excess water from overflowed rivers or lakes), springs, seeps and fens (groundwater discharge out onto the surface), bogs and vernal ponds (rainfall or meltwater). Wetlands are reservoirs of incredible biodiversity and can be important carbon sinks, depending on the specific wetland. They need to be considered in our attempts to mitigate the impacts of climate change. I could do a whole series focusing just on different types of wetlands!

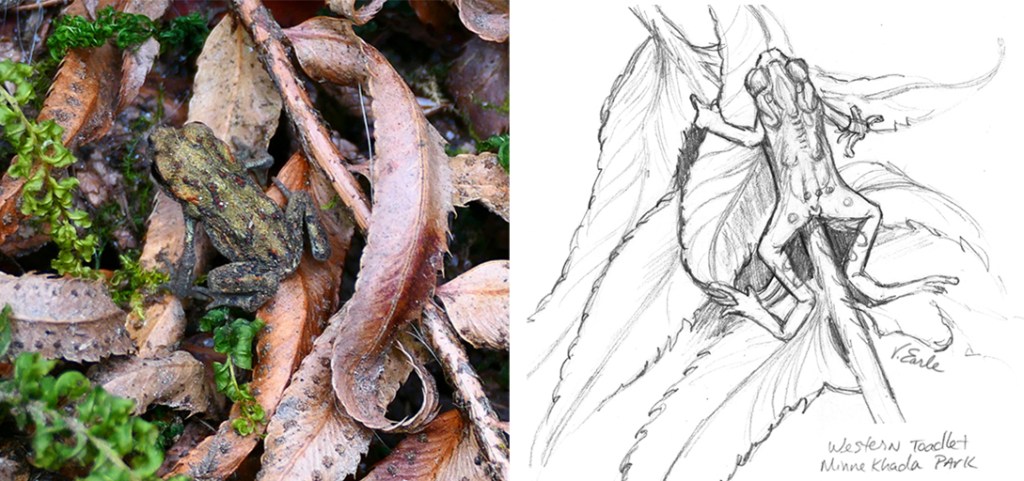

Minnekhada Regional Park is located in northeast Coquitlam, British Columbia, alongside Pitt-Addington Marsh and the Pitt River. It is over 200 hectares in size and is made up of wetland marshy areas, dense forest, and hills. I made a trip in August to witness the Western toad migration – when tadpoles transform into toadlets and make their way to new homes high up in the forest. I was delighted to see these tiny amphibians on their epic journey, along with blue dasher dragonflies. Both are listed as threatened species due to a combination of threats including loss of habitat, increased urban development, pollution, and changes in water levels. Species of Conservation Concern are those that are scarce or infrequently encountered.

Western toads use three different types of habitats during their life cycle: breeding sites along shallow bodies of water, ideally with sandy bottoms; terrestrial habitats in the forest or grasslands during the summer; and hibernation sites during the winter, where they stay in underground burrows up to 4 feet deep. The toadlets are so small! Some were the size of my thumbnail! It was incredible to find them all over the trails, climbing up very steep terrain making their way into the forest. Minnekhada is a perfect location for them. The photo and sketch below are of toadlets climbing up sword fern fronds during their journey to higher ground.

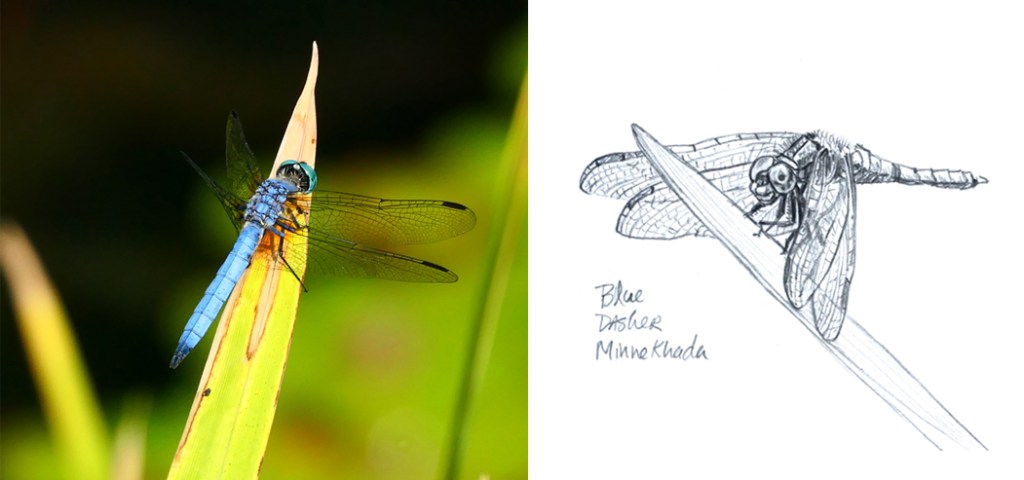

Blue Dasher Dragonflies. There are 87 species of dragon and damselflies in British Columbia. Of those, 23 species are considered rare or endangered. Dragonfly populations have adapted and survived for more than 300 million years and rely on still or slow-moving water for survival. They are natural residents in wetlands and can be spotted flying around lakes, marshes, and bogs. The Blue Dasher is one of a kind – it’s the only member of its genus and the largest member of the skimmer family. They are voracious predators of insect pests and important food sources for many other species. One dragonfly can eat hundreds of mosquitos in a single day. The Blue dasher below was an agreeable subject, coming back often to its perch and sitting still while I sketched it.

Wetland Mandala Design

I visited various wetlands throughout the Lower Mainland to sketch, make colour notes and take reference photographs for this mandala. The design itself went through a number of iterations. Showing the selected species in a way that provides an interesting and interconnected design was both a joy and a challenge! I have learned so much during this process, not only about wetlands in general and the important species who live there, but also about conservation organizations and volunteer groups doing incredible work to save these ecosystems in our area.

The final design I have decided to move forward with is below. A keystone species for wetland environments is the beaver, so it has been placed in the centre. Endangered species include the Western toad, red-legged frog, Western painted turtle, blue dasher dragonfly, and the northern water shrew. The great blue heron has been recently added to the threatened/species at risk conservation list. The broadleaf arrowhead, also known as wapato, is a plant of cultural importance to First Nations communities of the Lower Mainland. Cattails are important for wetland ecosystems. They create wildlife habitat, shelter for birds, food and cover for fish and for the insects they eat as well as helping stabilize the soil. Other species I have included are: the sandhill crane, marsh wren, spirea, anise swallowtail butterfly and various water insects/invertebrates. This final design is based on a triangular format. Triangles represent balance, harmony, equilibrium and strength and I feel it works well for this mandala both symbolically and from an artistic point of view.

This project is supported by the Artists for Conservation Rob and Sharon Butler Art Explorers Grant. This grant has allowed me to develop this series of paintings that I have been thinking of for quite some time. Thank you, Rob, Sharon and AFC!